The views expressed are those of the authors at the time of writing. This information does not constitute, and should not be construed as, an offer of advisory services, securities or other financial instruments, a solicitation of an offer to buy any security or other financial instrument, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell a security or other financial instruments in any jurisdiction.

By Kirsten Morin & Peter Mooradian, Partners, Co-Heads of Venture Capital

The inclusion of venture capital in a diversified investment program can be among the most compelling ways to obtain exposure to investments in the “innovation economy”. While an investor can gain “plain vanilla” exposure to the technology and healthcare sectors through the public markets, we believe only venture capital allows investors to tap into the incredible value creation potential of category-defining companies at their most formative stages.

However, the venture capital market poses unique and formidable challenges for investors. Specifically, we think investors need to:

- Identify VC managers with the highest probability of generating outperformance,

- Access funds that are highly oversubscribed, and

- Devote a material amount of their time, resources, and capital to build and manage a sufficiently diverse portfolio of VC funds.

So how does one navigate this labyrinth? We believe a venture capital fund-of-funds strategy (“VC FoF”) is a practical and sensible way to address these challenges for many investors. Further, and most importantly, it is our belief that a VC FoF can deliver performance that is comparable to that of a direct VC program, and do so in a risk adjusted manner, even after taking into account its additional layer of fees. This paper takes a closer look at the challenges of venture capital investing and how a properly constructed VC FoF effectively addresses them.

The Importance of Manager Selection1

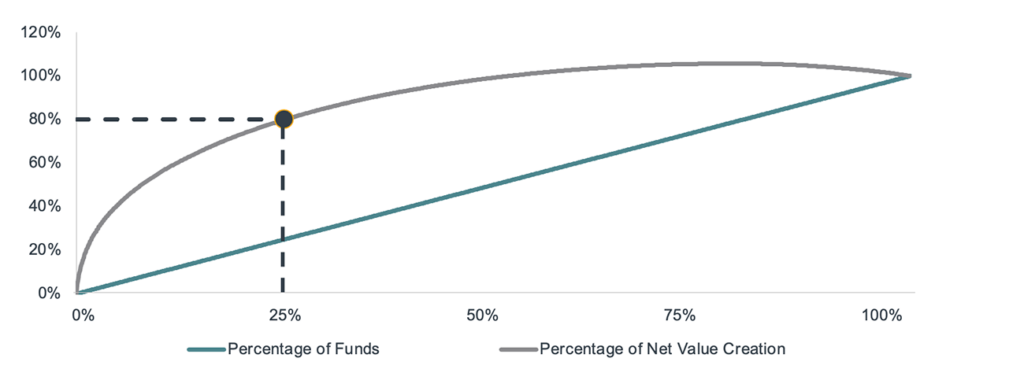

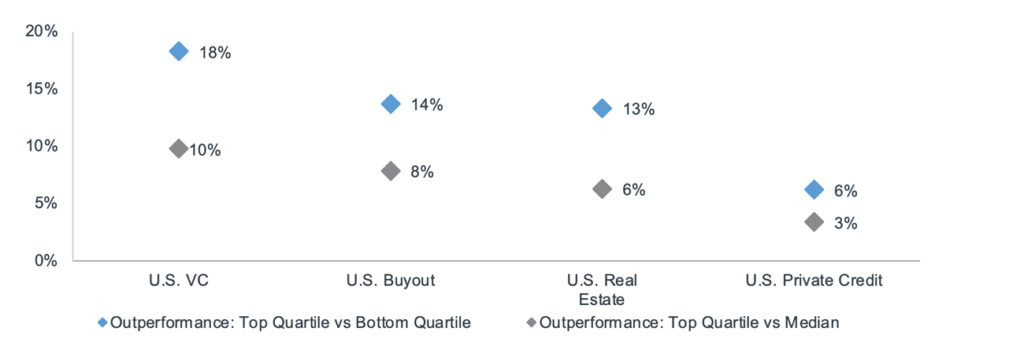

Manager selection is a critical component in driving the potential for outperformance, particularly in venture capital, where a select number of outlier companies drive total industry level performance. With only a select number of venture capital funds likely to invest in such companies, there is a material difference between the performance of the highest performing venture capital funds and all others. This dynamic is exemplified by the distribution of returns across the venture capital universe, as depicted in Exhibit 1, which shows that more than 75% of the venture capital industry’s Net Value Creation2across the 2001-2015 vintage years (“VYs”) has been generated by just 25% of fund managers. The importance of manager selection is also apparent in the outperformance of top-quartile venture capital funds, which in this data set have substantially exceeded the median and lower quartile by 1,000 and 1,800 basis points, respectively. The dispersion of returns for other private asset classes is materially smaller, as shown in Exhibit 2, and smaller still when compared to public equity and bond funds.3 Simply put, when it comes to VC, we believe manager selection is crucial for success.

Exhibit 1: Concentration of Net Value Creation4

1 Provided for illustrative purposes only, the information provided is at an industry level and no representation is being made about any specific investment or about any current or prior HighVista product performance. The past performance of a given strategy, group, or industry is not indicative of future results.

2 Provided for illustrative purposes only, “Net Value Creation” is created by MSCU Private Capital Indexes and is defined as gain on investment and uses a neutrally-weighted data set that assumes equal amounts of invested capital by each contributing fund within the MSCI Private Capital Indexes Manager Universe of US VC Funds from 2001 – 2015 (890 funds total) as of 9/30/2023.

3 Source: JP Morgan’s Q4’23 Guide to Alternatives.

4 Data is equal weighted provided by MSCI Private Capital Indexes as of 9/30/23, data includes 890 U.S. VC funds from vintage years 2001-2015.

Exhibit 2: Outperformance of Top Quartile Managers by Asset Class5

5 Source: MSCI Private Capital Indexes as of 9/30/23, represents horizon IRR data for 2001-2015 VY funds in each respective asset class as calculated by MSCI Private Capital Indexes. The number of funds included in the MSCI Private Capital Indexes U.S. Manager Universe is as follows: VC – 890 funds, Buyout – 709 funds, Real Estate – 507 funds, and Private Credit – 397 funds.

However, not all venture managers are created equal. Why? The data suggests that there is persistence in venture performance that is not only attributable to a sound investment strategy but also to the strength of a firm’s brand. Top-performing venture capital managers who, by definition, have helped their portfolio companies achieve successful exits in our experience are typically the first call for the next generation of entrepreneurs, giving those venture capitalists a first look at promising companies of the future. Previously successful company founders serve as critical references in this process, acknowledging the material value provided by their venture investors, be it sourcing talent, introducing potential customers, attracting additional capital, and so forth. This dynamic leads to what we think of as a reinforcing cycle of “success begetting success”, creating a halo effect for the leading franchise venture managers.

The persistence of venture capital returns is thus borne out in the numbers. Research from R. Harris et al. found that venture capital managers repeated first-quartile performance in their next fund 45% of the time.6 By comparison, buyout managers did so just 35% of the time. While past performance is not indicative of future performance results, past manager success appears to be an attribute that reinforces the importance of manager selection. To repeatedly identify top-performing venture capital managers, we believe an LP needs to be ensconced in the market and possess a keen understanding of the defining characteristics of promising venture capital funds. The challenge becomes even more daunting when evaluating emerging managers without fully established track records. A specialized VC FoF team that devotes all of its time and energy to venture capital investing we think is likely to be better positioned to source and evaluate managers than investors that cannot dedicate sufficient resources to remain current on a constantly evolving venture capital manager ecosystem.

6 Harris, R., Jenkinson, T., Kaplan, S., Stucke, R. (2023) Has persistence persisted in private equity? Evidence from buyout and venture capital funds. Journal of Corporate Finance.

The Access Challenge

Investing in venture capital is more than just a manager selection exercise. After identifying the most promising managers, an LP must forge strong relationships to distinguish its capital and gain access to oversubscribed funds. Building deep relationships with high-quality GPs entails significant time and effort. This is no simple feat because the top-performing venture capital funds are often closed to new investors as any appetite for fresh capital and successor funds will be more than satisfied by their existing LPs.

A long-standing, successful VC FoF typically has established relationships with some of the most access-constrained venture capital fund managers, enabling its LPs to benefit from those relationships immediately. This characteristic is in contrast to building a direct venture capital fund program from scratch over a period that will span many years.

The Diversification Imperative

Having identified that a limited number of portfolio companies drive industry performance, we think a single venture capital fund is unlikely to capture most of them and, as a result, it is our experience that a rifle-shot approach to venture capital rarely works. Rather, top-performing companies tend to be spread unpredictably across multiple leading venture capital funds. If an LP elects to invest in a single venture capital fund, it could potentially miss participating in the category defining companies that are likely to have the potential to drive industry returns in any given cycle, resulting in underperformance over time.

By investing in a basket of venture capital funds, an LP can increase the likelihood of capturing the outperformers, and thus the potential to improve overall returns, while simultaneously reducing the risk of underperformance. On this point, our research indicates that the potential benefits of diversification are maximized when a portfolio reaches 15-20 underlying fund commitments with any further diversification appearing to yield negligible incremental benefits.

Of course, building diversification requires capital. Most direct venture capital funds require minimum commitments of $5-10M. As such, a direct venture capital portfolio can require $50-100M of total commitments per fund cycle to achieve a sufficient level of diversification. In contrast, VC FoFs typically have lower investment minimums, sometimes as low as $1M, providing desired diversification with a significantly lower capital outlay.

A Word on Fees

The practicalities of using a VC FoF for manager selection, access, and diversification are apparent to us. However, at times LPs and certain consultants have an understandable negative reaction to the additional layer of fees and the potential resulting drag on performance.

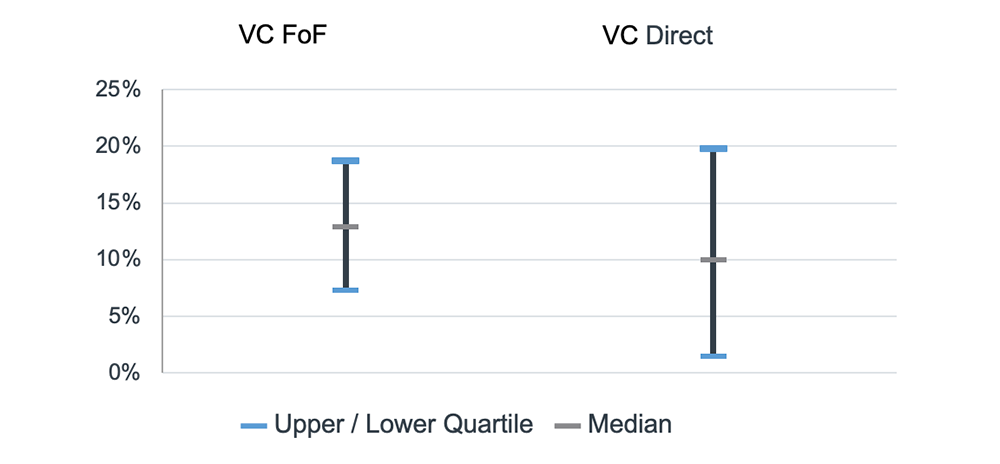

However, based on venture capital FoF benchmarks as reported by MSCI Private Capital Indexes, upper quartile VC FoF performance is comparable to that of direct venture capital funds, even after accounting for the additional layer of fees. The same is true for median benchmark performance. Further, a VC FoF offers additional benefits that can help to influence desired outcomes including benefits derived or attributed to manager selection, access, and diversification. MSCI Private Capital Indexes benchmark data suggests that lower quartile VC FoFs outperform their direct counterparts by up to 600 basis points. Simply put, a VC FoF has the potential to deliver outperformance comparable to a direct venture capital program while offering additional benefits that can help to influence desired outcomes including benefits derived or attributed to manager selection, access, and diversification.

Exhibit 3: VC Performance FoF vs. Direct7

7 Data provided by MSCI Private Capital Indexes as of 9/30/23, data includes 890 U.S. VC funds from vintage years 2001-2015. Please refer to MSCI Private Capital Universe – Essential Facts for further details on performance methodology.

Conclusion

To gain exposure to the innovation economy and the value creation that comes with it, we believe a diversified investment program should include an allocation to venture capital. However, successfully building a venture allocation is a substantial undertaking. To do so, we think LPs must identify, access, and construct a diversified portfolio of the leading venture capital fund managers. Such an effort requires a disproportionate amount of time and dedicated resources, given that venture capital tends to be, appropriately, a smaller component of LP investment programs. Since VC FoF’s can generate performance comparable to that of direct venture capital portfolios, a VC FoF could be the smart choice for many LPs seeking venture capital exposure.

Kirsten Morin, Partner & Co-Head of Venture Capital

Kirsten is a Partner at HighVista Strategies and co-leads the Venture Capital program. She joined HighVista in 2023 as part of its acquisition of the abrdn US private markets business. Kirsten is a member of the Venture Capital Investment Committee and is involved in all aspects of the investment process. She has worked on the HighVista Venture Capital funds for nearly two decades, at abrdn and previously as a Principal at FLAG Capital Management prior to its acquisition by abrdn in 2015. Prior to joining FLAG in 2005, Kirsten worked for IBM in a variety of analytical roles. Kirsten received a BS from Babson College.

Peter Mooradian, Partner & Co-Head of Venture Capital

Peter is a Partner at HighVista Strategies and co-leads the Venture Capital program. He is a member of the strategy’s investment committee and he joined HighVista in 2023 as part of its acquisition of the abrdn US private markets business. Prior to HighVista, Peter had joined abrdn Inc. in 2019 following a 15 year career at Cambridge Associates where he served as Managing Director, Private Investments Research and co-led the venture capital and growth equity research practice. Previously, Peter devoted his early career to increasingly senior private equity and technology-related strategy and corporate finance roles at firms such as The PrivateEdge Group, a division of State Street Corporation. Peter received a BA from Colgate University and an MBA from the Amos Tuck School at Dartmouth College.

Important Disclosure

This presentation is provided for informational purposes only, is general in nature, and is meant only to provide a broad overview for discussion purposes. The information expressed herein reflects the judgments and opinions of the authors at the time of writing, does not purport to be complete, has been excerpted from HighVista investor communications, and no obligation to update or otherwise revise such information is being assumed. Historical data, statements, and other information contained herein is believed to be reliable but no representation or warranty is made as to its accuracy, completeness or suitability for any specific purpose. Some information used in the presentation has been obtained from third parties through various published and unpublished sources. HighVista does not warrant the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of the information and materials contained in this document and expressly disclaims liability for any expressed or implied representations, errors, or omissions in such information, materials or any related written or oral communications transmitted to the recipient. Use of information from sources referenced herein does not represent any sponsorship, affiliation, or other relationship between HighVista and any other company or entity and does not constitute an endorsement. This information does not constitute, and should not be construed as, an offer of advisory services, securities or other financial instruments, a solicitation of an offer to buy any security or other financial instrument, or a recommendation to buy, hold or sell a security or other financial instruments in any jurisdiction. Any reproduction or distribution of this presentation, in whole or in part, or the disclosure of its contents, without the prior written consent of HighVista Strategies LLC is prohibited.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. References to specific securities, issuers, indexes, and strategies are for illustrative purposes only, does not represent any sponsorship, affiliation, or other relationship between HighVista and any other company or entity, does not constitute an endorsement, and are not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations to purchase or sell such securities. Nothing contained herein constitutes investment, consulting, legal, tax, accounting, or other advice, nor is it intended to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Information provided herein is based upon HighVista data and analysis and is believed to be accurate as of the time of writing, but no representation or warranty is made herein. Statistical and mathematical measures of performance and risk measures based on past performance, market assumptions or any other input should not be relied upon as indicators of future results. The strategies described in this presentation may exhibit the potential for attractive returns, however they also involve a significant degree of risk, including the risk of total loss of investment. A broad range of risk factors, individually or collectively, could cause a strategy to fail to meet its investment objectives No investment process, strategy, or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risk in any market environment.

THIS PRESENTATION CONTAINS FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS WITHIN THE MEANING OF THE U.S. FEDERAL SECURITIES LAWS. FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS ARE THOSE THAT PREDICT OR DESCRIBE FUTURE EVENTS OR TRENDS AND THAT DO NOT RELATE SOLELY TO HISTORICAL MATTERS. FOR EXAMPLE, FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS MAY PREDICT FUTURE ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE, DESCRIBE PLANS AND OBJECTIVES OF MANAGEMENT FOR FUTURE OPERATIONS, PERFORMANCE AND RISK AND MAKE PROJECTIONS OF REVENUE, INVESTMENT RETURNS, RISK CALCULATIONS OR OTHER FINANCIAL ITEMS. FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS CAN GENERALLY BE IDENTIFIED AS STATEMENTS CONTAINING THE WORDS “WILL,” “BELIEVE,” “EXPECT,” “ANTICIPATE,” “INTEND,” “CONTEMPLATE,” “ESTIMATE,” “ASSUME,” “TARGET” OR OTHER SIMILAR EXPRESSIONS. SUCH FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS ARE INHERENTLY UNCERTAIN, BECAUSE THE MATTERS THEY DESCRIBE ARE SUBJECT TO KNOWN (AND UNKNOWN) RISKS, UNCERTAINTIES AND OTHER UNPREDICTABLE FACTORS, MANY OF WHICH ARE BEYOND CONTROL. NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES ARE MADE AS TO THE ACCURACY OF SUCH FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS.